When political realities come up against ecological realities, the former must be changed because the latter cannot.

Read MoreAbout That Vision Thing

National Parks

When political realities come up against ecological realities, the former must be changed because the latter cannot.

Read MoreThis Part 3 suggests ways to partially—but significantly—bring back the magnificent old-growth forests that have long been lost.

Read MoreUnderstanding the history of public lands is useful if one is to be the best advocate for the conservation of public lands.

Read MoreThis is the third of three Public Lands Blog posts on 30x30, President Biden’s commitment to conserve 30 percent of the nation’s lands and waters by 2030. In Part 1, we examined the pace and scale necessary to attain 30x30. In Part 2, we considered what constitutes protected areas actually being “conserved.” In this Part 3, we offer up specific conservation recommendations that, if implemented, will result in the United States achieving 30 percent by 2030.

Top Line: Enough conservation recipes are offered here to achieve 50x50 (the ultimate necessity) if all are executed, which is what the science says is necessary to conserve our natural security—a vital part of our national security.

Figure 1. The Coglan Buttes lie west of Lake Abert in Lake County, Oregon. According to the Bureau of Land Management, it “is a dream area for lovers of the remote outdoors, offering over 60,000 acres of isolation,” and the land is “easy to access but difficult to traverse.” The agency has acknowledged that the area is special in that it is a “land with wilderness characteristics” (LWCs), but affords the area no special protection. Congress could designate the area as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System (Recipe #24), or the Biden administration could classify it as a wilderness study area and also withdraw it from the threat of mining (Recipe #1). Source: Lisa McNee, Bureau of Land Management (Flickr).

Ecological realities are immutable. While political realities are mutable, the latter don’t change on their own. Fortunately, there are two major paths to change the conservation status of federal public lands: through administrative action and through congressional action.

Ideally, Congress will enact enough legislation during the remainder of the decade to attain 30x30. An Act of Congress that protects federal public land is as permanent as conservation of land in the United States can get. If properly drafted, an Act of Congress can provide federal land management agencies with a mandate for strong and enduring preservation of biological diversity.

If Congress does not choose to act in this manner, the administration can protect federal public land everywhere but in Alaska. Fortunately, Congress has delegated many powers over the nation’s public lands to either the Secretary of the Interior or the Secretary of Agriculture (for the National Forest System), and—in the sole case of proclaiming national monuments—the President.

Potential Administrative Action

Twenty-two recipes are offered in Table 1 for administrative action by the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Agriculture, or the President. The recipes are not mutually exclusive, especially within an administering agency, but can be overlapping or alternative conservation actions on the same lands. While overlapping conservation designations can be desirable, no double counting should be allowed in determining 30x30. A common ingredient in all is that such areas must be administratively withdrawn from all forms of mineral exploitation for the maximum twenty years allowed by law.

Mining on Federal Public Lands

An important distinction between federal public lands with GAP 1 or GAP 2 status and those with lesser GAP status is based on whether mining is allowed. Federal law on mineral exploitation or protection from mining on federal public lands dates back to the latter part of the nineteenth century with the enactment of the general mining law. Today, the exploitation of federal minerals is either by location, leasing, or sale. The administering agency has the ability to say no to leasing and sale, but not to filing of mining claims by anyone in all locations open to such claiming.

When establishing a conservation area on federal lands, Congress routinely withdraws the lands from location, leasing, or sale. Unfortunately, when administrative action elevates the conservation status of federal public lands (such as Forest Service inventoried roadless areas or IRAs, Bureau of Land Management areas of critical environmental concern or ACECs, and Fish and Wildlife Service national wildlife refuges carved out of other federal land), it doesn’t automatically protect the special area from mining.

Congress has provided that the only way an area can be withdrawn from the application of the federal mining laws is for the Secretary of the Interior (or subcabinet officials also confirmed by Congress for their posts) to withdraw the lands from mining—and then only for a maximum of twenty years (though the withdrawal can be renewed). A major reason that particular USFS IRAs and BLM ACECs do not qualify for GAP 1 or GAP 2 status is that they are open to mining.

More Conservation in Alaska by Administrative Action: Fuggedaboutit!

The Alaska National Interest Lands Act of 1980 contains a provision prohibiting any “future executive branch action” withdrawing more than 5,000 acres “in the aggregate” unless Congress passes a “joint resolution of approval within one year” (16 USC 3213). Note that 5,000 acres is 0.0012 percent of the total area of Alaska. Congress should repeal this prohibition of new national monuments, new national wildlife refuges, or other effective administrative conservation in the nation’s largest state. Until Congress so acts, no administrative action in Alaska can make any material contribution to 30x30.

Potential Congressional Action

Twenty-two recipes are offered in Table 2 for congressional action. The recipes are not mutually exclusive, especially within an administering agency, but can be overlapping or alternative conservation actions on the same lands. However, they should not be double-counted for the purpose of attaining 30x30. A commonality among these congressional actions is that each explicitly or implicitly calls for the preservation of biological diversity and also promulgates a comprehensive mineral withdrawal.

Bottom Line: To increase the pace to achieve the goal, the federal government must add at least three zeros to the size of traditional conservation actions. Rather than individual new wilderness bills averaging 100,000 acres, new wilderness bills should sum hundreds of millions of acres—and promptly be enacted into law. Rather than a relatively few new national monuments mostly proclaimed in election years, many new national monuments must be proclaimed every year.

For More Information

Kerr, Andy. 2022. Forty-Four Conservation Recipes for 30x30: A Cookbook of 22 Administrative and 22 Legislative Opportunities for Government Action to Protect 30 Percent of US Lands by 2030. The Larch Company, Ashland, OR, and Washington, DC.

Crown Zellerbach timber executive: “We knew in the 1950s we had to log it then, or it would be a national park by now.”

Read MoreI am bearish on the prospect of establishing any new national parks in Oregon, save perhaps one that would be a hell of a long shot. I am semi-bullish on the possibility of modest additions to Oregon’s only national park. But I am bullish on the chances of designating several new National Park System units in Oregon.

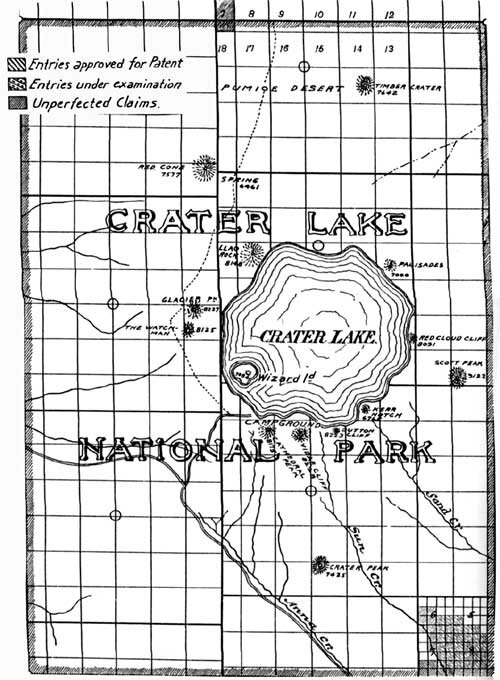

Read MoreNo new national park proposal in Oregon has made it past the finish line since the establishment of Crater Lake National Park in 1902. Oregon’s only national park has had two very modest additions since then, in 1932 and in 1980.

Read MorePart 2 discusses multiple failures to establish additional national parks in Oregon.

Read MoreThere are national parks and then there are other units of the National Park System—all administered by the National Park Service. The United States has 62 national parks. It has another 357 units that are also part of the National Park System but go by another name (national whatevers). Herein we focus on the one national park in Oregon.

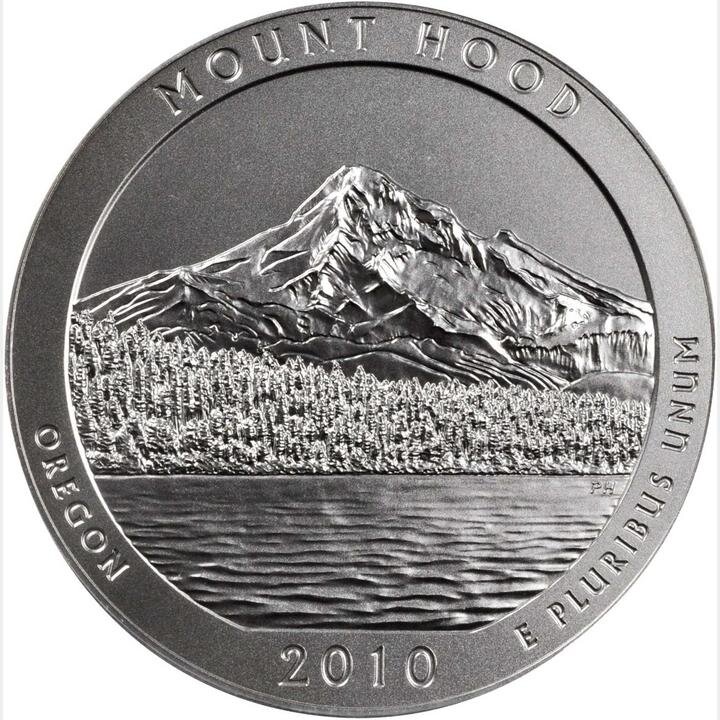

Read MoreIn 2019, Senator Ron Wyden and Representative Earl Blumenauer met with various stakeholders at Timberline Lodge to discuss the future of greater Mount Hood. Senator and Representative: What’s your plan?

Read MoreVery high on my bucket list is to see a California condor in the wild (Figure 1), ideally over Oregon. If my timing is good and the condors cooperate, this could happen.

Read MoreFig. 1. Crabtree Lake in Crabtree Valley, which contains some of the oldest trees in Oregon, is in the proposed Douglas Fir National Monument, located in Oregon’s Cascade Mountains. Source: David Stone, Wildlands Photography. Previously appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness (Timber Press, 2004), by the author.

Less than a week after President Trump signed the Oregon Wildlands Act into law (as one of many bills in the John D. Dingell, Jr., Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act), Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Representative Earl Blumenauer (D-3rd-OR) convened an Oregon Public Lands Forum on Monday, March 18, 2019.

Read MoreSeveral mostly good public lands conservation bills have been introduced in the 115th Congress (2017–18) but languish in committee, unable to get a vote on the floor of the House or the Senate.

Read MoreIn early January 2018, the National Park Service instituted a new parking reservation system for Muir Woods National Monument near San Francisco. Actually, it is more accurate to say “for Muir Woods National Monument in the San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland, CA Combined Statistical Area (CSA).” The 554-acre national monument includes 240 acres of magnificent old-growth coast redwood forest. An estimated 1.2 million people visit each year, drawing mainly from the ~8.8 million and increasing humans of greater San Francisco. The mere 232 parking spaces just cannot handle the crowds anymore. It will now cost $8 per vehicle, along with the $10 entrance fee, to park your car if you want to take in Muir Woods. If you don’t plan far enough ahead, you might be able to catch a shuttle ($3) from downtown Sausalito, but those require reservations as well. Farewell, dear spontaneity.

Mount Hood from Lost Lake, which has not been lost for a very long time. Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives

Though four presidents expanded Muir Woods National Monument after Theodore Roosevelt set aside the first 295 acres in 1908, the expansion of the monument has not kept up with the expansion of the nearby population. It’s not like there are adjacent stands of majestic old-growth coast redwoods next door just waiting for inclusion in the monument. Naturally, the coast redwood has a very limited range on Earth (about two million acres in a narrow strip from just south of Big Sur to just north of the Oregon-California border, with 95 percent having been clear-cut).

The National Park Service is doing similar rationing in Yosemite and Haleakala National Parks and is considering the same for Zion and Arches National Parks.

There are two overarching reasons to conserve, restore, and increase the acreage of public lands:

· to provide for the adequate functioning of ecosystems and watersheds across the landscape (and seascape) and over time so as to provide the vital goods and services that only nature can provide to this and future generations

· to allow this and future generations adequate opportunities to directly and indirectly engage in recreational (pronounced “re-creational”) pursuits that support and renew the mind, body, and soul

The former—the provision of adequate nature for ecosystem functioning—is extremely difficult but not impossible. The latter—the provision of adequate nature for recreation—is not only extremely difficult but also may be impossible if the human population continues to grow like cancer.

Providing Adequate Nature: Supply and Demand Problems

As to the amount of land and water humans need to conserve and restore in order to provide for nature and her vital goods and services, Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson makes a compelling case in his greatest book, Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. Wilson’s recommendations come through the lens of species requirements. To exist, species need what they need. It’s not negotiable.

Regarding the provision of adequate nature for recreation, it’s not so much a supply problem as a demand problem. Increasingly, there are too many humans seeking to recreate in the same places at the same time. To a degree, more public lands could be reclaimed for recreational purposes, but, hopefully, not at the expense of the first overarching reason. More national recreation areas should be established on public lands (here is a list of some that and could be established in Oregon) and more private lands should be reconverted to public lands upon which to put more recreation areas. However, demand for natural recreation areas outstrips supply both because demand is out of control and because supply is inherently limited.

In general, there are too many people on Earth for our own collective good, and it’s getting worse. Human population continues to further outstrip the long-term carrying capacity of air, water, and land—and even the human requirement for elbow room. Unless this growth is soon stopped and then reversed, all bets are off.

The supply of natural recreation areas is inherently limited by considerations of both proximity and uniqueness. Most humans live in cities, and there is only so much land and water that can be used for human recreation. While I benefit greatly from knowing that the vast Brooks Range in northern Alaska is there, I—and most others—won’t be visiting it. Instead we mostly tend to visit natural recreation areas closer to home. With regard to uniqueness, there is only one Mount Hood near the Portland-Vancouver-Salem, OR-WA CSA and only one Mount Rainier near the Seattle-Tacoma-Olympia, WA CSA. Conjuring up another Cascade peak to satisfy the demand for natural recreation is not possible.

Negotiating Increasingly Crowded Spaces

The Oregon I grew up in and am growing old in used to be a lot less crowded. Over the decades my enjoyment of natural recreation areas has been a negotiation, mainly in the form of strategic retreat and lowered expectations. For example, in my youth, one could reasonably expect a hot spring in the western Cascades, and certainly in Oregon’s Sagebrush Sea, to be uncrowded. Today, a visit to a forested hot spring near the Willamette Valley will be an overcrowded experience.

To get the solitude that to me and many others is a vital part of natural recreation, I started shifting my recreation in both time and space. For a while, if I went to hot springs during the week, and then late at night (or even better, early in the morning), and then finally in the dead of winter during heavy rains or snow, I could obtain the requisite solitude. There were also hot springs that were an eight- to ten-hour drive from the Willamette Valley, accessible by relatively poor roads, where I could find solitude. That worked for a while, but the crowds from LaBendmondville (aka the Bend-Pineville CSA)—which is nothing more or less than the present easternmost demographic extent of the Willamette Valley—discovered not only those hot springs but also those lava caves, fault-block ranges, post-Pleistocene lakes and other recreational attractants of Oregon’s Sagebrush Sea.

In 2000, I helped persuade Congress to extend special protections to Steens Mountain (background). We tried to include the vast desolately enchanted landscape to the each, including Mickey Hot Springs (foreground), but had to settle for a mere mineral withdrawal. At least there will never be geothermal exploitation of Mickey and several other other springs. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

In response to increasing overpopulation, what came to Muir Woods will eventually be coming to a natural recreation area near and/or dear to you. But actually, reversing overpopulation is not that hard. If all those who wanted children would limit themselves to two, what is now out of control could soon be back in control.

“Birds should be saved for utilitarian reasons; and, moreover, they should be saved because of reasons unconnected with dollars and cents. A grove of giant redwoods or sequoias should be kept just as we keep a great and beautiful cathedral. The extermination of the passenger-pigeon meant that mankind was just so much poorer. . . . And to lose the chance to see frigate-birds soaring in circles above the storm, or a file of pelicans winging their way homeward across the crimson afterglow of the sunset, or a myriad of terns flashing in the bright light of midday as they hover in a shifting maze above the beach-why, the loss is like the loss of a gallery of the masterpieces of the artists of old time.”

This least outdoors-loving American president makes me appreciate the most outdoors-loving president, Theodore Roosevelt. TR spent many a night outside of a bed under the open stars, including three nights in the Sierra with John Muir. Before TR left office in 1909, he had established, sometimes with Congress and sometimes without: 51 bird reservation, four national game reserves, five national parks, 18 national monuments, and 150 national forests. I fear the losses to be toted up when Trump leaves office.

Read MorePresident Trump signed an executive order on April 26, 2017, that directs Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke to review sixty-two of the last three presidents’ national monument proclamations, dating back to 1996. The review will result in a final report in four months that “shall include recommendations, Presidential actions, legislative proposals, or other actions consistent with law.”

The administration is interested in either totally abolishing, reducing in size, and/or weakening the protections for national monuments. Those prerogatives belong to Congress. If Trump tries, he’ll get a multitude of tweets saying, “See you in court!”

Read MoreCrabtree Lake in Crabtree Valley, home to some of the largest and oldest trees in Oregon, located on western Oregon public lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management, in Linn County, is part of the proposed Douglas-Fir National Monument. Photo: David Stone, Wildlands Photography.

There is no question that an Act of Congress can eliminate, shrink, or weaken a national monument proclaimed by a president pursuant to authority granted by Congress. What Congress giveth, Congress can taketh away. The property clause of the U.S. Constitution (Article 4, Section 3, Clause 2) ensures that. Yet in fifty-five Congresses over the past 110 years, Congress has rarely acted to eliminate, reduce, or weaken a national monument proclamation by a president.

Read MoreIf one rationally considered the probability of succeeding at elevating a discrete piece of federal public land to the status of a congressionally designated national what-have-you area (wilderness, wild and scenic river, national park, national monument, national recreation area, national wildlife refuge, or such), one might never embark on the voyage. One usually has to overcome an entrenched establishment of industry, locals, and government that doesn’t want things to change. Yet, conservationists proceed anyway, and if they are smart, clever, and persistent (with emphasis on the latter) enough, they do find success. It often takes a generation to change the world, or even a part of it.

Read MoreThe climate, the oceans, species, watersheds, ecosystems, landscapes, cultures, and economies that depend on federal public lands all depend upon the 45th president of the United States having a bold public lands conservation agenda.

While the Property Clause (Article 4, Section 3, Clause 2) of the United States Constitution vests the power over federal public lands with Congress, as the legislative branch Congress cannot be expected to oversee the day-to-day operation of the federal public lands. Therefore, Congress has broadly set policies and then directed specified entities in the executive branch to carry them out. For example, the vast number of congressional statutes pertaining to the National Forest System make reference to the secretary of agriculture (or in some cases the chief of the Forest Service) as the responsible official empowered and directed by Congress to carry out the statute. As most federal public lands are under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior, the secretary of the interior (and occasionally the director of the Bureau of Land Management, the Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, and so on) is similarly empowered or directed.

Though these cabinet officers or agency heads are appointed by the president, they must be confirmed by the Senate before they can assume the office. When it comes to federal public lands, these public land officials have two masters, the president who gave them their job and the Congress—in particular the committees of jurisdiction (the House of Representatives’ Committee on Natural Resources and the Senate’s Committee on Energy and Natural Resources)—who gave them their marching orders.

In some cases, Congress has granted the president certain powers over federal public lands, most notably to proclaim national monuments or to allow or disallow the development of offshore oil and gas. The president and her cabinet and agency heads should use these and other powers granted to them by Congress to advance the cause of conservation of the public lands for the benefit of this and future generations.

What follows is a public lands conservation agenda that the next president could implement without any additional Acts of Congress. It’s unfortunate to have to assume Congress missing in action when it comes to the conservation of federal public lands, but it is. (I hear Congress was more dysfunctional just before the Civil War, but I wasn’t there.)

1. Keep it in the ground.

Federal public lands account for about a quarter of all U.S. fossil fuel production and therefore one-quarter of the carbon dioxide pollution from those sources. To help avert the worst effects of climate change, an immediate ban on new federal fossil fuel leases should be imposed, nonproducing current leases should be allowed to expire, and existing producing leases should be bought back. Doing such will not only help mitigate climate change, it will also prevent harm to the nature that depends on federal public land. Several conservation organizations, including the Center for Biological Diversity, are leading the Keep It in the Ground campaign for federal public lands.

2. Ban renewable energy development on federal public lands.

While less damaging to the climate, the supposed “green” electrons that come from renewable energy projects on federal public lands are better thought of as “light brown” electrons. Concentrated production of renewable energy from wind, solar, and geothermal is as damaging to nature as concentrated production of nonrenewable energy from coal, oil, and gas. Poxing the federal public lands with wind towers or covering them with photovoltaic panels renders that public land parcel worthless for conservation. Public lands have a higher and better use than industrial sites for any kind of energy development. For example, both the desert tortoise and photovoltaic panels find suitable habitat in the California desert. However, solar panels can live—better actually—on roofs in town, while the desert tortoise cannot.

3. Double the National Wildlife Refuge System.

Under existing congressional authorities, the secretary of the interior by secretarial order or the president by executive order can establish new or expand existing national wildlife refuges. These expansions can come from federal public lands currently administered by the Bureau of Land Management or encompass an area of nonfederal land so that the lands can later be acquired by donation or purchase from willing sellers.

4. Proclaim more national monuments.

In the Antiquities Act of 1906, Congress gave the president authority to proclaim national monuments. Hundreds of millions of acres of federal public lands in the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone and many tens of millions of acres of onshore public lands are worthy of national monument designation. Most presidents have mostly proclaimed national monuments as they were leaving office; but given the general dysfunction of Congress, national monuments should be proposed and proclaimed early and often. For some onshore areas, it may be appropriate for the president to announce her intention to proclaim a national monument well in advance in order to spur Congress to act to conserve an area in ways that can be superior to a national monument proclamation. For example, President Obama’s interest in proclaiming a national monument in Idaho in 2015 prompted Congress to establish 275,000 acres of wilderness in central Idaho—a bill that had been languishing for nearly a decade.

5. Save Wyoming and Alaska federal public lands in other creative ways.

Part of the 1950 congressional deal to combine Grand Teton National Monument (est. 1929) and Jackson Hole National Monument (est. 1942) to create Grand Teton National Park excluded Wyoming from any future presidential proclamations of national monuments. In Alaska, since enactment of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980, the president’s authority to proclaim new national monuments is limited to ones less than 5,000 acres in size. Much of the 73 million acres of BLM holdings in Alaska and the 18 million in Wyoming are in need of elevated conservation. With the Antiquities Act rendered useless in these two states, the president could establish new national wildlife refuges or direct her secretary of the interior to do so. In addition, the president could issue executive orders directing the BLM to manage particular areas of public lands for conservation purposes and to prohibit harmful activities.

6. Keep it in the forest.

A very large fraction of the excess atmospheric carbon came not from the burning of fossil fuels but from the conversion of native forests to cities, farmlands, and clear-cuts. Forests on federal public lands need to be protected in order to remove excess carbon from the atmosphere and store it securely.

The United States owns tens of millions of acres of “moist” (not subject to frequent fire) forest types in southeastern Alaska, western Washington, western Oregon, northern California, northern Idaho, and northwestern Montana. These moist forests act as huge and secure stores of carbon, and they also sequester additional carbon back to the biosphere from the atmosphere. Most are within the National Forest System, but some significant areas are administered by the BLM. By executive order, the president could direct the secretaries of agriculture (Forest Service) and interior (BLM) to set aside “carbon reserves” that contain moist forests to conserve already-stored carbon and to maximally sequester additional carbon to help ameliorate the effects of climate change. Many of these moist forest stands consist of older (mature and old-growth) trees that are best suited to resist and adapt to climate change.

7.Keep it in the grass.

Temperate grasslands store more carbon on average than temperate forests, according to a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The difference is that most of the carbon in a forest is aboveground, while most of the carbon in a grassland is belowground. Livestock grazing and other destructive agricultural practices have not only severely reduced aboveground carbon stores (otherwise known as plants) but also allowed the release of much belowground carbon. Carbon reserves such as those recommended for moist forest types could also be established to protect public land deserts and grasslands.

8. Raise royalties on federal energy revenues.

While the best thing for the world’s climate is for the federal government to collect no royalties from fossil fuel production on federal public lands as it should no longer be allowed, until that time the taxpayers should receive a fair return on something private entities are allowed to sell. A report by the Center for Western Priorities notes that the royalty paid to the federal treasury for fossil fuel production from federal lands is 12.5 percent of revenues. Compare this to the 16.75 percent charged by Wyoming, Utah, Montana, and Colorado, or the 18.75 percent charged by New Mexico and North Dakota, or the 25 percent charged by Texas for fossil fuel production from state lands. The federal government receives 18.75 percent for offshore oil and gas.

Besides representing a fair percentage of revenues, the royalty should factor in the social cost of carbon (SC-CO2). SC-CO2 is measured in $/tonne and includes—but is not limited to—the cost of changes in net agricultural productivity, adverse impacts on human health, property damage from flooding, and changes in the energy system due to climate change. It is the cost to society of placing CO2 in the atmosphere. Burning a barrel of oil (42 U.S. gallons) emits 0.43 tonnes of CO2. West Texas Intermediate (WTI Crude Oil, a benchmark for oil prices) is trading for around $50/barrel. Ifthe SC-CO2 is $36/tonne CO2, adding the social cost of carbon to the price of a federal barrel of oil would increase its price by ~$16. It probably wouldn’t offset the special tax breaks afforded to fossil fuel producers that are permanently embedded in the U.S. tax code, but it would help level the playing field for sustainable and renewable forms of energy.

9. Withdraw all scenic- and recreation-classified wild and scenic rivers from mining.

In its wisdom (pronounced “compromise”), Congress specified in the 1968 Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA) that only the segments of wild and scenic rivers classified as “wild” would be withdrawn from the application of the federal mining laws. Those segments classified as “scenic” or “recreational” are not protected by WSRA from mining. The difference is that a “wild” segment generally has no roads in its corridor, whereas a “scenic” segment may have a road crossing its corridor and a “recreational” segment a road along its corridor. If a stream is worthy of inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (NWSRS), it’s worthy of not being mined. Some—but far from all—such stream segments have been withdrawn from mining by the secretary of the interior under the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act withdrawal provision for the maximum allowed twenty years. All of the NWSRS should be so protected from mining.

10. Link mineral withdrawals to management plans.

The Forest Service and the BLM develop land and resource management plans under the authority of the National Forest Management Act and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA), respectively. In such plans the agencies designate lands for conservation and sometimes prohibit such things as logging, road building, grazing, off-road vehicles, fluid mineral leasing, and other activities that would harm the values for which the area is being managed. However, under the Mining Law of 1872, an area of federal land may only be protected from hardrock (gold, etc.) mining if the area has been “withdrawn” pursuant to the withdrawal provision of FLPMA. The president should direct the BLM and the Forest Service to promptly apply to the secretary of the interior for such mineral withdrawals, and she should direct the secretary to promptly withdraw them.

“If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them. ”

It’s time for the BLM to have its own comprehensive land conservation system: a National Desert and Grassland System. Congress should place appropriate BLM lands into a system of national deserts and national grasslands similar to the National Forest System.

Read More